Whether or not California’s wage and hour laws apply to work performed out of state generally depends upon the circumstances of employment. In Bernstein v. Virgin America, Inc., 227 F. Supp. 3d 1049 (N.D. Cal. 2017), the court rejected the argument that the “job situs” of the plaintiff was determinative as to whether the California Labor code applied. Instead, the Bernstein court explained that: “[i]nstead of considering principal ‘job situs’ in a vacuum, the California Supreme Court has endorsed a multifaced approach.

Beware of Unconscionable Mandatory Employment Arbitration Agreements

AVOID THE COMMON MISCLASSIFICATION OF NON-EXEMPT EMPLOYEES UNDER THE ADMINISTRATIVE EXEMPTION

Can I Be Evicted For Something Like That? Really!

1. The Notice.

The Notice purports to modify the residential tenancy and Lease under Civil Code Section 827. It purports to make any breach of the Lease, no matter how immaterial or trivial, a material breach of the Lease justifying (1) forfeiture of the Lease and (2) termination of the tenant’s right to possession. The provision reads something like: “3. Renter agrees that Renter’s performance of and compliance with each of the terms of the rental agreement constitute a condition on Renter’s right to occupy the premises. Any failure of compliance or performance by Renter shall allow Owner to declare a forfeiture of this agreement and terminate Renter’s right to possession. Any breach of the contract is a material breach.”

The Notice is not signed or dated by the tenant, nor does it reflect the tenant’s express written consent in any manner. The Notice is signed by the landlord only. Similarly, the Notice was not negotiated by the landlord and tenant; the Notice was prepared unilaterally by the landlord.

Can I be evicted for a slight or immaterial breach of the lease now? As discussed in more detail below, no. The Notice is invalid – and the tenant should reject it – because a landlord may not evict a residential tenant because of the tenant's breach of a lease where the terms in dispute are materially different from the original lease and unilaterally imposed by the landlord and not agreed to by the tenant in writing. Moreover, an immaterial breach of a residential lease governed by the Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance (“RSO”) may not be made ipso facto material, such that the breach warrants forfeiture and the landlord’s right to possession, simply by inserting words to that effect in the lease.

2. The Notice As a Whole Is Invalid.

The entire Notice is invalid on its face because a landlord may not unilaterally change the terms of a residential lease subject to the RSO and then attempt to evict based on a violation of those unilateral terms. The tenant must agree in writing to the additional covenant, and the tenant must knowingly consent, without threat or coercion, to each change in the terms of the tenancy.

The landlord is engaging in a tricky scheme that has been squarely and repeatedly rejected by California courts. This scheme was rejected in at least six cases before the Court of Appeal and the Los Angeles County Superior Court, Appellate Division, two of which have published opinions, and by amendment to the RSO. See L.A. Mun. Code § 151.09.A.2.(c); Boston LLC v. Juarez, 245 Cal.App.4th 75 (2016); NIVO 1 LLC v. Antunez, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. 1 (2013); see also Y&Y Investment Group, LLC v. Lopez, Case No. BV029752; Y&Y Investment Group, LLC v. Farela, Case No. BV029713; Babay v. Cadenas, Case No. BV029139; Westhill Management v. Correa, Case No. BV028271.

The cases above were brought by a well-known Los Angeles UD mill/attorney, Allen R. King, Esq., who marketed that he had a “secret way to evict a rent control tenant.” The “secret” was to serve a unilateral Notice of Change of Terms of Tenancy containing a forfeiture clause for immaterial or trivial breaches of the lease that could later be used to evict the tenant or force the tenant to leave for a trivial breach. The landlords then served three-day notices for trivial breaches of the subject leases and later sought forfeiture of the lease and possession of the premises.

In the NIVO 1 case, the landlord served a Notice of Change of Terms of Tenancy to render all breaches material. That Notice stated: “3. Renter agrees that Renter’s performance of and compliance with each of the terms of the rental agreement constitute a condition on Renter’s right to occupy the premises. Any failure of compliance or performance by Renter shall allow Owner to declare a forfeiture of this agreement and terminate Renter’s right to possession. Any breach of the contract is a material breach.”

The NIVO and Boston decisions are the result of this “secret.” The courts in NIVO and Boston analyzed and ultimately rejected the “materiality” clause specifically and the two Notices generally, declaring them to be invalid.

“’[A] lease may be terminated only for a substantial breach thereof, and not for a mere technical or trivial violation.’ This materiality limitation even extends to leases which contain clauses purporting to dispense with the materiality limitation.” Boston LLC, supra, 245 Cal.App.4th at 81 (internal citation omitted).

Los Angeles Municipal Code sections151.00 et seq. prohibit a landlord from bringing an unlawful detainer action based on a unilateral change in terms of the tenancy. “A. A landlord may bring an action to recover possession of a rental unit only upon one of the following grounds: [¶]. . . [¶] 2. The tenant has violated a lawful obligation or covenant of the tenancy and has failed to cure the violation after having received written notice from the landlord, other than a violation based on [¶]. . . [¶] (c) A change in the terms of the tenancy that is not the result of an express written agreement signed by both of the parties. For purposes of this section, a landlord may not unilaterally change the terms of the tenancy under Civil Code Section 827and then evict the tenant for the violation of the added covenant unless the tenant has agreed in writing to the additional covenant. The tenant must knowingly consent, without threat or coercion, to each change in the terms of the tenancy.” L.A. Mun. Code § 151.09 subd. A.2.(c).

The NIVO court addressed this very provision of the RSO, writing that “LARSO, Los Angeles Municipal Code section 151.00 et seq., prohibits a landlord from bringing an unlawful detainer action based on a unilateral change in terms of the tenancy.” NIVO 1 LLC v. Antunez, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. 1, 4 (2013).

Here, the Notice is unilateral, and the tenant has not consented in writing to the Notice. It is, therefore, invalid as a whole under NIVO and Section 151.09.

3. Section 3 of the Notice – the “Materiality” Clause – Is Invalid.

In NIVO, the property supervisor testified that she posted and mailed to defendant a notice of change of terms of tenancy. As noted above, the notice read: “‘3. Renter agrees that Renter’s performance of and compliance with each of the terms of the rental agreement constitute a condition on Renter’s right to occupy the premises. Any failure of compliance or performance by Renter shall allow Owner to declare a forfeiture of this agreement and terminate Renter’s right to possession. Any breach of the contract is a material breach.’ (Italics added.).” NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 4.

She further testified that defendant failed to comply with the notice and did not obtain renter’s insurance, as required by Paragraph 17 of the lease. A three-day notice to perform this covenant or quit was served, and an unlawful detainer action followed. See NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 3. “[T]he unilateral change by the plaintiff-landlord sought to alter the terms so that the failure to maintain insurance would be deemed a material breach such that it would result in a forfeiture of the lease agreement.” NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 4 (emphasis added). The court concluded that “[s]uch a change of terms is invalid under the provisions of LARSO [the Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance].” NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 4.

Moreover, the same “materiality” provision is invalid under black letter contract and lease law. The NIVO court stated: ““Whether a breach is so material as to constitute cause for the injured party to terminate a contract is ordinarily a question for the trier of fact.” NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 4. “The distinction between a material and inconsequential breach is one of degree, to be answered, if there is doubt, by the triers of the facts.” NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 5.

The court went on to conclude:

Whether a particular breach will give a plaintiff landlord the right to declare a forfeiture is based on whether the breach is material. The law sensibly recognizes that although every instance of noncompliance with a contract's terms constitutes a breach, not every breach justifies treating the contract as terminated. Following the lead of the Restatements of Contracts, California courts allow termination only if the breach can be classified as material, substantial, or total.

NIVO 1 LLC, 217 Cal.App.4th Supp. at 5 (internal quotations omitted).

The Court of Appeal in Boston LLC v. Juarez, 245 Cal.App.4th 75 (2016) addressed a very similar “materiality” provision and concluded that a tenant’s breach of a Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance, L.A. Mun. Code, § 151.00 et seq., rental contract must be material to justify the landlord forfeiting the contract and terminating the tenancy. Boston LLC, 245 Cal.App.4th at 79. According to the Boston LLC court: “[c]ase law is clear as to what kinds of ‘failure to perform’ justify forfeiture. Courts have consistently concluded that a lease may be terminated only for a substantial breach thereof, and not for a mere technical or trivial violation.” Boston LLC, 245 Cal.App.4th at 81 (internal quotations omitted). This rule holds more true for RSO leases, as “[p]ublic policy and other considerations favor a materiality requirement, especially for an LARSO lease.” Boston LLC, 245 Cal.App.4th at 84.

Here, the landlord attempted to add the same unlawful and invalid “materiality” clause rejected by the NIVO and Boston courts and prohibited by the RSO. Consequently, Section 3 of the Notice – the “Materiality” clause – is invalid, and the tenant should reject it.

City of Los Angeles Approves New Rules for Airbnb and HomeAway

After years of debate, the Los Angeles City Council voted Tuesday to impose new rules on Airbnb and HomeAway rentals. Under the new rules, properly registered hosts could offer up their homes for up to 120 days per year. For more information read: L.A. approves new rules for Airbnb-type rentals after years of debate

NEW STUDY SUGGESTS AIRBNB FREQUENTLY MISUSED

California Labor Code Section 226.2 Mandates Compensation of Rest and Recovery Periods and Nonproductive Time to Employees Who Receive Piece-Rate Compensation

An employee may be paid by “piece-rate” or “piece work” compensation. Piece-rate or piece work compensation is defined as “[w]ork paid for according to the number of units turned out.” DLSE Enforcement Policies and Interpretations Manual § 2.5.1. Some examples of piece-rate or piece work compensation are:

1. Automobile mechanics paid on a “book rate” (i.e., brake job, one hour and fifty minutes, tune-up, one hour, etc.) usually based on the Chilton Manual or similar;

2. Nurses paid on the basis of the number of procedures performed;

3. Carpet layer paid by the yard of carpet laid;

4. Technician paid by the number of telephones installed;

5. Factory worker paid by the widget completed;

6. Carpenter paid by the linear foot on framing job.

DLSE Enforcement Policies and Interpretations Manual § 2.5.2.

California Labor Code § 226.2 went into effect on January 1, 2016, and includes new requirements for employers who pay employees on a piece-rate basis.

Fourth Circuit Rules That "Assault Weapons" Not Protected by Second Amendment

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals has ruled that military style "assault weapons," including certain semi-automatic weapons, are not protected by the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. In Kolbe v. Hogan, ___ F. 3d. ____, 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 2930, (4th Cir. 2017), which may be read here, the Court of Appeals upheld a Maryland law that outlawed certain assault weapons. Md. Code Ann., Crim Law § 4-303. The ban included over 40 identified weapons including the Colt AR-15, the Bushmaster semi-auto rifle, and the AK-47. Md. Code Ann., Crim Law 5-101(r)(2).

In Kolbe, the State of Maryland was sued by a number of gun rights activists supported by the NRA for violated the Second Amendment by enforcing the law. In response, the State of Maryland argued that the targeted assault weapons were weapons of war and therefore not protected by the Second Amendment. Both parties cited to the seminal United States Supreme Court decision of District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008), authored by Justice Antonin Scalia. The Fourth Circuit agreed with the State of Maryland..

Employers Must Defend their Employees From Lawsuits Even When Employees are at Fault

Thinking of Renting Out Your Place on Airbnb? That May Not Be a Good Idea if You Live in L.A.

Premises zoned residential, such as R1, R2 and R3, in the City of Los Angeles should not be rented through Airbnb or similar services.

Current zoning laws in the City of Los Angeles prohibit short-term rentals in residential zones, such as R1, R2 and R3. Residential zones given the “R” designation are intended to provide a quiet living environment, free of commercial, business and industrial activities. Operation of residential premises as a hotel, hostel, bed and breakfast, or similar commercial enterprise is not permitted under an R1, R2 or R3 designation. See L.A.M.C., Ch. I, Art. 2, §§ 12.03, 12.08, 12.09, 12.10. The Los Angeles Municipal Code lists allowed uses of these residential designations. Notably missing from the permitted uses is the use of residential premises as a hotel, hostel, bed and breakfast, or similar commercial enterprise

Homeowner's Associations Liable For Failure To Provide Access

HOAs may be liable to homeowners if they prevent or hinder a homeowner's right of ingress or egress.

Homeowners cannot be barred from ingress or egress (right of entry or exit) to their units and cannot be barred from physical access to their units, unless:

1. The HOA has a court order or an arbitration award;

2. Construction is in progress;

3. A hazardous condition exists; or

4. The unit is uninhabitable or red tagged. Civil Code §§ 4505, 4510.

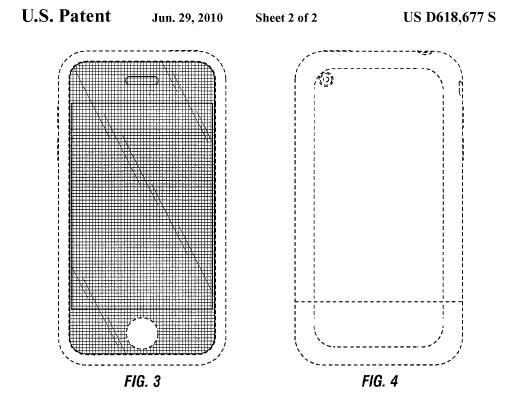

Supreme Court Reverses Apple's $399 Million Award Against Samsung

The Supreme Court has vacated Apple’s $399 million patent infringement damage award against Samsung. This substantial award was based on three Apple “Design Patents” which cover only “non-functional” aspects of the “design” or appearance of the IPhone such as the shape of the front and back of the phone. These design patents have nothing to do with the functionality of the phone. Still, Apple was able to convince the trial court that it should receive 100% of its claimed profits of its IPhone, not only those profits lost as result of Samsung’s infringement of the design. In fact, the district court refused to even allow Samsung to make the argument Apple’s profit on the design was far less than the profit on the entire IPhone.

The Supreme Court disagreed. Writing for a unanimous court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor ruled that should not have been prohibited from making the argument that Apple should have been limited to its profits on the design alone. See Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. v. Apple, Inc. Case No. 15-777 (December 6, 2016).

Inability to Pay High Arbitration Fees May be a Defense to Arbitration Agreements

Where a party to an arbitration agreement is financially incapable of sharing the costs of arbitration, the Court has discretion to retain jurisdiction over the action and deny arbitration. See Roldan v. Callahan & Blaine, 219 Cal.App.4th 87 (2013); see also Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1281.2. Confronted with the issue of whether plaintiffs could be excused from the obligation to pay fees associated with arbitration, the Court of Appeal concluded they could. Roldan, 219 Cal.App.4th at 95. “If, as plaintiffs contend, they lack the means to share the cost of the arbitration, to rule otherwise might effectively deprive them of access to any forum for resolution of their claims against [defendants]. We will not do that. Of course, as the trial court recognized, we cannot order the arbitration forum to waive its fees.” Roldan, 219 Cal.App.4th at 96.

Credit Card Arbitration Agreements Under Attack

The California Supreme Court is once again reviewing consumer credit card arbitration agreements.

In December 2014, the California Court of Appeal held in McGill v. Citibank, N.A. that California’s law against arbitrating claims for public injunctive relief under the Unfair Competition Law, the Consumer Legal Remedies Act and the False Advertising Law was preempted by the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). The appellate court declared that “the FAApreempts all state-law rules that prohibit arbitration of a particular type of claim because an outright ban, no matter how laudable the purpose, interferes with the FAA’s objective of enforcing arbitration agreements according to their terms.” Thus, the appellate court found in Citibank’s favor that arbitration agreements are enforceable even when they strip California credit card holders of the right to public injunctive relief. Now the California Supreme Court is reviewing that lower court ruling.